Cementist (sḗ-měnt’ist), n. 1. A worker in cement. 2. One who builds with: rough unhewn stone, pieces or chips of marble, using mortar; esp., a kind of strong mortar made with lime, or a calcined mixture of clay and limestone in plastic state that afterwards solidifies into an (un)natural rock.

3. Any human or animal in the practice for making bodies adhere to each other with a substance such as glue, sealing wax, mud, starch paste, gum etc.

4. A uniter and former of unions; that unites firmly, as persons in long friendship.

5. An explorer of the philosophical foundation of ethos

“Cement. – Middle English, cyment; Old French, ciment; Latin, caementum, and late Latin, cimentum. A contraction for caedimentum, meaning rough unhewn stone, the literal meaning being the product of cutting or chipping.”

The vestigial oils from an algal bloom rise to the ocean surface and froths into the foam that floats over your foot. The remnant sea foam of the proverbial concrete stoop once float over the foot of a crocodilia one hundred million years ago. From the beginnings of our primordial liquid past the concrete stoop emerged in its precursory form, more accurately it lived. This is because the primary ingredient of cement is limestone. And limestone is made up from the shells, or exoskeletons of tiny ocean life, once thriving in the prehistoric seas. As these life forms grow they harvest chemicals floating in the ocean water to synthesized a new compound, a secretion which forms their shell (calcium carbonate). After death their exoskeletons can dissolve but remains as calcium carbonate. It is this materials that becomes limestone.

Into the columns of the sea their remnant bones are scattered. They may sink where they lived in shallow seas or drift over the continental slopes and abyssal plains blown by tidal winds. Gradually this material can build up layer by layer into a thick calcareous ooze. Under the pressure of saltwater and sky and with much time this biologic sediment slowly hardens. Submerged below the ocean for a while the once oozing silts might one day bulge up into wrinkles on the curling face of earth. And from those airy parts of land you might obtain an oceanic limestone cement.

The micro-skeletons transformed and risen onto land is harvested, crushed, mixed with clay, cooked then re-crushed for truck, trowel and hand. Through human time it has served many purposes, facilitating new forms of the artificial cave, artificial like the mud spit nest of a swallow. Though to some, the swallows hollow is no artificial thing. Almost as ubiquitous as the essential water of life, cement continues its path beside us, plied among the landscapes of urban life. In the primordial expanse, the little ocean creatures could never have fathomed their destiny, even if they could. Poured into molds, grown up into the sky, looking out over the human beings below in a landscape of cemented stone; all glued up from a soup of unfathomable bones congealed onto land, living bones of the primeval oceans, and some who left behind a foam.

A little more on the difference between cement and concrete. Cement is the abstract glue material within the sidewalk that without would be pathway of rocks and sand. With the addition of water cement becomes like water that turns to ice and never back to water, but before and after it’s always, ‘cement’. So it changes, though it is the same, by name, like us. We cannot know cement, like we cannot truly know ourselves, but it’s all around us. When cement is combined with aggregates and mixed with water it creates the common gray manufactured stone polymer we all know (concrete), ubiquitous in the modern landscape, essential element of the good life.

Mud Home to High Rise

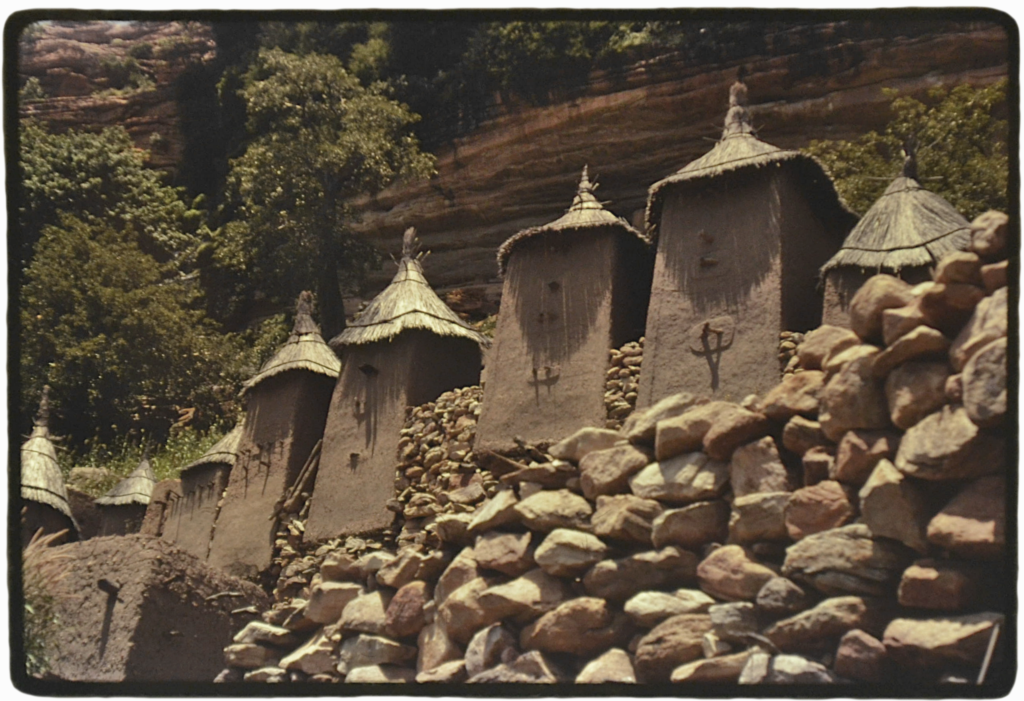

The first human cement was mud, as long as it contained a sufficient clay content. This was used to bind things together or simply as the building material itself. Theoretically, early people learned that mud by itself was mud, but not all types of mud were good, good mud needed the right amount of clay in it to be useful. When mixed with sticks and grass the mud became stronger, something new, a polymer. This was an early form of cement. A realization like this would likely lead the innovator to experiment further with new material, to play with different types of mud and additives. With no small effort, the first homes and vessels were formed. Simply by itself, the mud would not last in weather, so a roof was added. Necessity drove innovation, an industry of cementists was born. Undoubtedly ancient forms of cement were discovered all over the world in every society where people began building permanent structures. Various civilizations discovered their own version of cement independently, though undoubtedly recipes were also shared through the commingling of cultures, or stolen, especially when various peoples were absorbed into the bottom of a dominant culture.

One such story of cement involves the Nabataens. Originally a nomadic people of the Arabian Desert, the Nabataens later became a distinct and influential empire; partly from their ability to thrive in a difficult landscape, they were essentially oasis builders, facilitated in part by a new type of cement. Though it’s impossible to know exactly how ancient peoples like the Nabataens discovered the predecessor to modern cement, quicklime, there are probable theories. One involves a connection to the ceramics industry from its use of kilns. If the kiln or cooking pit was lined with limestone it’s possible the limestone rock could release CO2 transforming it into quicklime. This would be possible if the temperature was high enough. Cultures around the world discovered and manufactured quicklime, a white cementitious materiel commonly used to whitewash stone. This is technique is so ancient it isn’t clear who discovered it first or if it was discovered independently by various cultures. Many of the largest pyramids on both sides of the Atlantic were at one point covered with a limestone whitewash.

The Nabataeans even incorporated fine silica powder found in concentrated deposits as a methods to create waterproof cement. This type of additive is known as a pozzolan. In combination with specialized tools and tamping methods this new cement produced a water impervious concrete. This allowed them to capture and preserve the scant waters through a network of aqueducts and cisterns scattered throughout the Arabian desert. Hidden bellow the earths surface or in caves, liquid life was stored safely away from the heat. This new cement allowed them to live and thrive within an arid desert landscape, their own designed oases. Innovations like these have allowed desert dwelling peoples to thrive in harsh landscapes, long before air conditioners and portable spray fans.

Their wealth and prosperity didn’t go unnoticed though, and at some point in the continuum of history the Nabateans were annexed into the Roman empire. Romans are also known for their cement, and are famous for their use of pozzolans. The roman pozzolans were obtained from volcanic ash deposits scattered throughout the empire. One of these deposits was in the city of Pozzuoli, the materials namesake, near Mt. Vesuvius. These reactive materials were used only for the most important or architecturally complex structures. Aside from pozzolans some recipes listed animal fat, milk and blood as admixtures to improve the properties of concrete, there is some truth to this. Through centuries of experimentation the Romans were able to construct what is still the world’s largest non-reinforced concrete dome (Pantheon). Though not as tough as modern polymer concrete, many Roman concretes are more durable and longer lasting than the modern material. This is partly due to the lack of metal reinforcements which invariable rust and cause failure of the structure. Attributed to this durability is in part the pozzolan, but that didn’t explain the mysterious self healing ability of some Roman concretes. The long lost secret, quicklime, and a particular component of it called, a lime-clast. This material within quicklime dissolves overtime with rainwater water and relocates into cracks and voids like a mineral glue, thus preventing the crack from spreading. Some Roman concretes used in seawall construction points to the salt water in creating mineral growths that improve long term durability. Still, much remains unknown of Roman concretes and their techniques, there were innumerable types used for different purposes. Some Roman piers are still sitting around in the brine to this day. Modern cement would have crumbled long ago.

Quicklime cement was common in ancient times used by people such as the Nabateans, though until it could be proven its benefits are largely forgotten, or ignored. The benefits of pozzolans are not as recently discovered as the self healing ability of lime-clasts in but still they remain a ‘new material’, largely underutilized in the construction industry throughout the world. This is important because the use of pozzolans can reduce the use of cement, as cement is more energetically costly to produce. Cement production world wide contributes at most 8 percent to global CO2 emissions. At this moment, the most commonly used cement in the world is portland lime cement.

Cementist

On the urban horizon sits monoliths of cemented stone. Vertical, almost insurmountable mountains filled with something cash flow positive. Possibly all full up with yellow balloons passing away the time. When I look at them I can honestly say I’ve never see anybody inside looking out, I’m always looking. The largest of these now approaches a mass equal to the great pyramids of the world, complete with a Pharaoh-ish glossy patina, don’t forget the pyramids were once bright white. I always enjoy the view outside. Mirrored smooth stone and glass, a perfect surface rising above the lowland asphaltum and concrete walks frosted in rubber love. A new monolith stands high above for our visual pleasure, and other things. Humans inhabit this world of cement constructs, real and imagined. Behind liquid water there is concrete as the most consumed liquid on earth. Low on lumber we turn to manufactured stone to construct the contemporary cave. Concrete walls augment the space of our world into the indoor/outdoor. In form and function the space is cave-like, but becomes outdoor from the inclusion of living plants and light. All is well in the electrified hermit’s cave. From ancient complexity to modern mundane commonality, it cannot be both. One can easily forget what defines us.

There is no question a more accurate moniker is given by the outsider. So what would a turtle say about humans if one could speak to the other. From looking, it might see where we go to spend our time, and it would see us, or mostly not see us, because we spend the majority of our time inside lost in the sediment of our mind. And if it could read minds, the mind in which we all live and wonder, for why and what and how do I live. The mind of, ‘who am I?’. The mind of tireless searching for something solid to grasp onto, the search for a foundation to bind our purpose of self. Considering the evidence of what it gleaned, it might say this, and very slowly, ‘they are cementists’. And it would leave to eat some turtle food, and go on right ahead living as a turtle would, and do that without a wonder why, because the answer is so obvious, because its not actually a turtle.

Biological calcareous ooze (limestone) is not the only component of cement, though it is the main ‘active’ ingredient. More importantly though it is a link that connects cement to the beginning in the evolution of life, and also to the first of human alchemical cements. I am grateful to the people throughout history who have devoted their life to the material. Without the work of countless cementists, I could not do what I do on this planet, ‘the best of all possible worlds’.

1. Bertram Blount, William H. Woodcock, Henry J. Gillett, Cement (London: Longmans, 1920).

2. The History of Concrete and the Nabataeans. http://nabataea.net/cement.html/.

3. David Nicholas Buck, A Musicology for Landscape (New York: Routledge, 2017).

4. Marie Jackson, Paul Gabrielsen, How seawater strengthens ancient Roman concrete. (2017). https://unews.utah.edu/roman-concrete/.

5. Linda M. Seymour et al, Hot mixing: Mechanistic Insights into the durability of ancient Roman concrete (Science Advances, 2023).